When Chief Executive Carrie Lam addressed the Hong Kong press on August 13, she chose an alarming turn of phrase. “Look at our city and our home,” she said, apparently fighting back tears. “Could we bear to push it into an abyss where everything will perish?” As a puppet of the regime in Beijing, Lam has been known to make trips to the mainland for her orders, and so she may have access to some of the discussions taking place among the leaders of the Communist Party. Was her suggestion of a coming “abyss” more than just a dramatic choice of words?

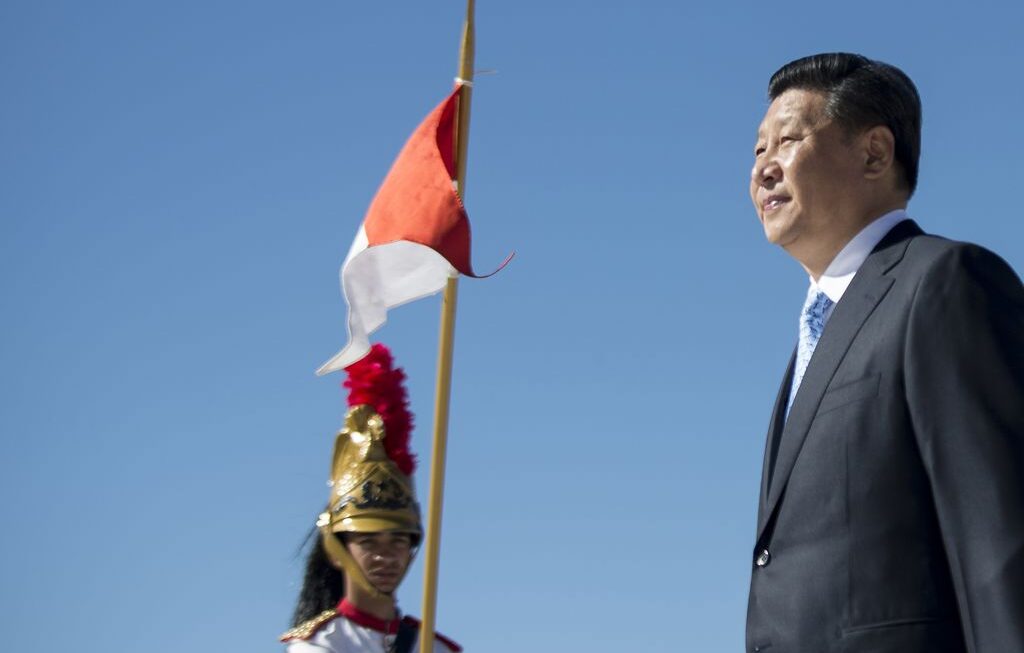

The Party already has 6,000 troops permanently stationed in Hong Kong, and now additional military units from the mainland are gathering in the south of China. Propaganda videos have shown scores of armoured personnel carriers en-route to Shenzhen, the megacity at the border, and the obvious implication is that they are being deployed in response to the ongoing protests. Dark hints were made in a public statement by the central government’s Hong Kong and Macau Affairs Office: “If the turbulence continues, the whole of Hong Kong society will pay the cost.” All of this would seem to indicate that Xi Jinping is prepared for a repeat of the Tiananmen Square bloodbath of 1989. And according to Charles Lipson, professor of political science at the University of Chicago, “there’s essentially nothing that can be done if the Chinese want to crack down on Hong Kong.”

There are reasons, however, to think that the outcome would be very different to Tiananmen Square. To begin with, there are the numbers: in 1989 the protests peaked at around 1 million (from a total Beijing population at the time of 6.7 million), while Hong Kong has already seen 2 million turn out (from a similarly-sized total population: 7.3 million). The number of protesters may yet rise, and so when the PLA tanks roll in, they will face enormous resistance. Then there is the mood: a small number of protesters have turned violent, and with good reason. On 21 July a gang of white-shirted CCP-sponsored triads stormed into Yuen Long train station and beat commuters with metal rods as they returned home from demonstrations – they even assaulted a pregnant woman, and children had to be hurried to safety. In the weeks after the incident some protesters armed themselves in the same way, fighting back furiously when accosted by white-shirted gangs in the streets. Protesters also broke into the Legislative Council and vandalised the building.

This atmosphere of rage was completely missing from Tiananmen Square in the build-up to the massacre. Chai Ling, one of the student leaders from 1989, has recalled that “We wanted to make a discovery, not a revolution… we were only trying to capture the attention of the monolithic, all-powerful leadership.”[1] Today’s Hong Kong protesters are not looking to make a “discovery.” They are fighting for their freedoms and in some cases their lives. The mood is panicked and desperate, and explicitly anti-PRC. Black-clad Hongkongers twice removed the Chinese flag and tossed it into the waters of Victoria Harbour, while others raised the old colonial flag, indicating that they would happily accept a return to British rule if it meant escaping the talons of the Chinese Communist Party.

Their attitude is not surprising, considering how they have been treated. When crowds gathered outside Kwai Chung and Tin Shui Wai police stations to call for the release of arrested demonstrators, the reaction of the authorities was remarkable. At Kwai Chung a police officer threatened the crowd with a shotgun, and at Tin Shui Wai fireworks were launched at bystanders from an unidentified black vehicle. The police have been filmed charging into subway stations and shooting activists at point blank range (not with live ammunition – yet), and they have been filmed disguising themselves as demonstrators at Hong Kong International Airport and then carrying out brutal assaults, pinning protesters to the floor in pools of their own blood before arresting them. On August 11 a female medic was hit in the eye with a beanbag round fired from a police weapon – she had been wearing safety goggles, but they shattered instantly, and now she faces the possibility of blindness in her right eye. On August 31 police stormed train carriages at Prince Edward station and beat random passengers, many of whom had not been involved in the demonstrations.

There is also anger at the treatment of protesters once they have been arrested. One woman has described how she was subjected to a 30-minute strip search while male police officers crowded outside the room to watch. Meanwhile several demonstrators have been charged with ‘rioting’, which can lead to a ten-year prison sentence, while the small number of triads arrested after the Yuen Long incident (men actually caught on camera causing grievous bodily harm) face the trivial charge of ‘unlawful assembly’. The hypocrisy is explicit, the abuse is shameless, and the mood will only grow more volatile in response.

When it comes to tactics, there is no comparison with 1989. The students at Tiananmen Square were brave, smart, and organised, but they were completely inexperienced. Once the crackdown came, there was little chance of them mounting any kind of defence. Today’s Hongkongers, on the other hand, are wily veterans of the 2014 Umbrella Revolution, and no doubt some of the older ones also took part in the 2003 protests. They have learned from the mistakes of the past. Now they adapt to circumstances with a speed and ingenuity that keeps them one step ahead of the authorities. They have no leaders, instead using the internet forum LIHKG to decide strategy. They take inspiration from Bruce Lee’s motto “Be water,” moving quickly from location to location guerrilla-style, flowing across the city in waves orchestrated by messages on Telegram. The Communist Party has never dealt with this new breed of protester, and will find it difficult to second-guess tactics.

Dialogue with Beijing is of course impossible. Chai Ling may have seen Deng Xiaoping’s government as “monolithic” and “all-powerful” back in the 1980s, but it was puny in comparison to Xi Jinping’s hulking global superpower. The Communist Party will not move an inch, and Hong Kong is home to angry millions who will not move either. Some of the latter must have realised that they have nothing to lose by prolonging the protests. Once everything dies down and ‘order’ is restored, then the Communist Party is likely to severely punish many of those involved, kidnapping them to the mainland and conjuring up imaginary charges in the usual fashion. The Party is already ramping up the rhetoric, describing the demonstrations as “close to terrorism,” and there can be little doubt that participants will be dubbed actual ‘terrorists’ in the aftermath. In order to avoid such a fate, many protesters will want the chaos to continue. This means that civil war could be on the cards.

Officers recently raided a flat and found 30 smoke bombs, but it would make sense for the protesters to begin amassing a far more potent armoury. The thought will not have escaped them. As one of their banners stated, “We need the 2nd Amendment.” There may be dispute over the continued relevance of the Second Amendment when it comes to the United States, but Hong Kong provides us with a perfect example of what Madison, Jefferson & co. had in mind when they argued for the necessity of a “well-regulated militia.” The Chinese Communist Party is the very archetype of a tyrannical state, and in such cases the people need to be able to defend themselves.

If a crackdown comes, it will be chaotic, bloody, and protracted. A senior police officer in Hong Kong has pointed out that there is no precedent for interoperability between mainland forces and the Hong Kong police. The Party never imagined that it would be facing this situation, and so no protocols have been established. In the heat of battle we could even see conflicts develop between the military and the police. This would make Carrie Lam’s vision of a coming “abyss” seem even more appropriate.

Our best hope is that international pressure and the watching eyes of the world cause Beijing to stay its hand, perhaps leading to a stalemate. In the end, we may find that the deciding factor is economic. The argument has been made in some quarters that Hong Kong’s Umbrella Revolution failed for one very simple reason: it didn’t hurt the Chinese economy. In a perceptive article for The Diplomat, Tyler Y. Headley and Cole Tanigawa-Lau suggested that the earlier political protests of 2003 were only successful because they effectively shut down the economy and caused millions of dollars’ worth of damages. Hong Kong’s stock index is vital to China, and so in the end the government had no choice but to grant democratic concessions. This bodes well, because the economic impact of the 2019 protests is likely to be huge. Australia has already seen a surge of interest in its millionaires-only visa program, and it’s the Hong Kong glitterati who are interested.

And so the Chinese leadership finds itself in a difficult position. What happens next will depend on whether Xi Jinping is able to swallow his pride. “For the Chinese Communist Party, the continuing crisis in Hong Kong is not only a direct challenge to its authority but also damaging to its domestic prestige and international reputation,” says Adam Ni, a China researcher at Macquarie University in Australia. “Essentially, Beijing just doesn’t have any simple short-term answers to the current impasse. Beijing’s Hong Kong problem is here to stay.”

Notes

[1] Chai Ling – A Heart for Freedom: The Remarkable Journey of a Young Dissident, Her Daring Escape, and Her Quest to Free China’s Daughters (Tyndale House Publishers, Illinois, 2011), p104